Report from the viewing of two strong documentaries from the fight against ISIS by Bernard-Henri Lévy

On a calm spring evening – with the sun still out – arriving at Bremen Theatre to see the two documentaries filmed in the midst of war against Daesh, as the famous French journalist and philosopher calls ISIS, I am met by several heavily armed policemen – in full combat uniform (bullet proof vests and huge machine guns).

By Bente D. Knudsen

The sight is a starch reminder that, although we are thousands of miles away, in peaceful Denmark, in a way, we are also in danger. Or at least this evening’s film-producer is.

The theatre fills up – the event is sold out. No Danish politicians are in sight (is Denmark not part of the alliance against ISIS?), however, the French ambassador is there.

The atmosphere is one of intense expectation, certainly since the first documentary we are to see, Peshmerga, is shown for the first time in Denmark, despite being out last summer after its Canne’s Film Festival screening.

Peshmerga , the name of the Kurdish defence forces, who in the film at times are seen in sneakers and without helmets (the lack of which proves fatal for an officer in the film who dies from being shoot in the head) are protecting the Kurd’s of northern Iraq and neighbouring countries — in a vast region commonly called Kurdistan.

In the film they are seen leading the charge against ISIS on the ground along a 1,000 km long boarder, with air support from the U.S. and other allied nations.

The film is intense, with shooting and explosions, dry arid dusty landscapes, and totally devastated small villages, villages which were already poor and simple before the war, now just a mas of shattered bricks and scattered debris.

If for no other reason, the documentary is worth seeing as it gives an insight into the living conditions, and the waste of war, on people who did not have much before, and have even less now.

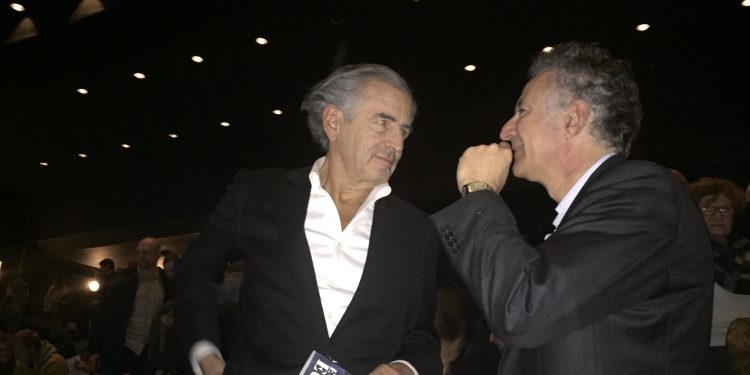

There is no doubt in the documentary and the speak given, on whose side Bernard-Henri Lévy is, but as he says afterwards in the interview with Danish journalist Allan Holm:

“I am showing what I saw and what I filmed, while I was there, it was not my aim, nor would it have been possible as I would probably have been shot, to enter into the ISIS territory to ask them, what was going on inside their heads.”

Having had to fight for their land throughout much of the last century, and having suffered a major massacre when Saddam Hussein used chemical weapons against the Kurdish population of Halabja in 1988, the Kurds are familiar with war and its many repercussions.

They are also, according to Bernard-Henri Lévy, a Muslim population truly in favour of secularism, human rights and equal rights of women and men.

The documentary follows amongst other a women’s only regiment during training and in combat, something unthinkable in most Arab countries, and who, as the speak says seam panic amongst ISIS:

“The female soldiers are feared by ISIS, as ISIS soldiers believe they will not be allowed into paradise to get their reward of virgins if they are killed by a female Peshmerga soldier.”

A surprising element in the documentary is the appearance of a famous female Kurdish singer, in full make-up and immaculately set hair , who is seen encouraging the dusty and uniformed soldiers. Somehow surreal and comforting at the same time.

We are also let in very close when soldiers are wounded and their comrades, desperately try to help them, literally load them rather helplessly onto pick-up trucks and hold their hands while they drive away to find help, as at most of the front posts, there are no medics with up-to date equipment. This is another thing, the Peshmerga, contrary to the general Iraqi forces also seen in the documentary, are hopelessly ill equipped, with old arms and hand held missile firing ramps and no head or ear protection.

The film also lets us hear the dream of the Kurdish soldiers fighting that they will one day be allowed to have their own independent state – and to be able to unite the Kurd’s living in several national states into one Kurdish State.

During the interview, which takes place before the screening of the second documentary, “The Battle of Mosul”, Bernard Henri Lévy issues a chilling warning to the audience (and the world listening?), once ISIS is defeated, what will happen in this region and with the Kurd’s.

“Are preparations being made to help the region into stability, and to prevent revenge between the Sunni and Shiites. Will if find peace and prosperity because the fractions – united because of war against a common enemy – are able to work together and understand and respect each other’s differences and human rights or will it sink into another kind of chaos and disaster?”

The second documentary, The Battle of Mosul, does not really leave us reassured. The documentary follows the battle to recapture Mosul in October last year and until January 2017 and films the Kurdish units and the Iraqi special Golden Division forces during the first months of the strategically complex operation.

At the end, the Peshmerga leave the fight for Mosul city to the Iraqi Special Forces, as they have paved the way to the entrance of Mosul, but leave the better equipped forces to enter the city – which as the speak explains is not Kurdish territory, and apparently, none of the Allied forces want the Kurd’s there for the final entrance to the city.

The documentary ends with a picture of an Iraqi special forces tank – on whose roof stands a soldier wearing a jacket with the Nazi swastika engraved on it.

No explanation is given for this addition to the uniform – and leaves the audience with incomprehension and a certain chill.